Cenk Uygur Founder The Young Turks

Papers and magazines are in a world of trouble. Classifieds are gone, their ad rates and share of the market are unjustifiable. They have to start charging incrementally for articles read online otherwise the whole thing is going to collapse. Television still has a lot of time and money left, but its days are also numbered %u2013 not TV as a concept but the networks. The main competitive advantage of the networks was reach; now YouTube is in every home. Tick, tock.Jeremy Silver Creative adviser Technology Strategy Board

The greatest opportunity online for media companies that have been in the business of commissioning programmes is to transform themselves into businesses that create and exploit their own intellectual property. These businesses need to develop direct relationships with their audiences and build brand values in the approach, presentation and style of their productions to generate direct dialogue, loyalty and ultimately consumer sales. Production companies will have to negotiate contracts that allow them to retain online and international rights %u2013 and broadcasters will need to open up their contracts in recognition of this. Those that fail to brand themselves and create broader online and non-UK followings will struggle.Nick Appleyard Digital Britain programme lead Technology Strategy Board

We propose that those concerned about the viability of their current operating models should first build their understanding of how their customers prefer to use their content and services, and then redesign their monetisation strategy accordingly.

Nicole Yershon, Director Ogilvy Labs

The survivors who will flourish will be the businesses who are open to change or collaboration with experts, without an enormous middle layer that still thinks that just doing the "day job" is acceptable. All platforms will be relevant %u2013 youth probably covers all areas from mobile, social media, gaming and IPTV. We mustn't get too much in our bubble of "digital excellence" %u2013 there are still many who get home from work at 6pm, have their dinner and are ready and sitting on the sofa, waiting for the BBC to serve them EastEnders at 7.30pm.Gerd Leonhard media futurist and author

There are a few things that are on their way out, and that includes monopolies that have outlived their usefulness, the concept of "selling copies" as a business model, "protecting rights" as the way of making money, and using friction to get payments. Most major record companies have a good chance of hitting the wall: they do way too little, way too late, and are still in love with controlling what consumers do, which prevents them from getting on with anything. My hunch is that the music industry will be 60-70% independent in five years.Google will do very well, so will Facebook (in my view, the next BBC), Apple, Amazon and Twitter. News media can do well if they embrace the switch to digital "reading" and cross-media content consumption. The main thing is to resist the temptation to charge too much while setting up hurdles that the users will hate. The future is in collaboration %u2013 not domination.

Philip Orwell Partner venturethree

I'm convinced that more and more people will pay directly for what they really want. So my mood is violently anti-ads and buoyantly �pro-subscription. The only way to be sustainable is to have great content and an easy way for people to get it, all delivered via a brand that lets you go deeper and further, if you want to.Steve Pomeroy Systems programmer MIT Mobile Experience Lab

In the world of mobile media, a relatively new delivery model has come about: the mobile store/market (the Kindle store, iPhone app store, Android etc). While an excellent tool for the company providing the mobile device, it takes away people's control of the �software and media on devices they own. If this continues to get out of hand, as it did back in July 2009 with Amazon remotely deleting books from people's devices, more people may become wary of this model.People could choose to subscribe to stores, much as they subscribe to a podcast or RSS feed. This would create a secondary "market of stores", which could help open up devices to a variety of niche stores, akin to the multitude of speciality stores already on the web.

Steve Purdham Chief executive We7

The big media companies will continue to be the big media companies, some will evolve and some will be absorbed but their balance sheets will continue giving them time to change and adapt. Any media company that adapts and embraces change and is not locked down to traditional economic structures can become sustainable. I still believe the unique model of the BBC has a �pivotal role to play in the localised UK market in showing the way forward.Rebecca Miskin General manager iVillage Networks

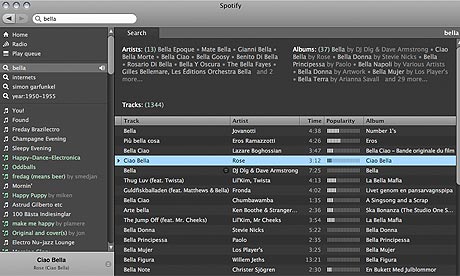

Most sustainable models are flexible and multi-tiered. Spotify, for example, has done a great job offering people an ad-funded and subscription model %u2013 each delivering value to users. Businesses will have to move toward a mix of revenue options that work for the value proposition they are offering their users.The Changing Media summit takes place on 18 March at Kings Place in London. For further information go to guardian.co.uk/changingmediasummit

Labels

Monday, 22 February 2010

What is the future shape of media? | Media | The Guardian

Warner Music may stop licensing songs to free online streaming sites | Music | guardian.co.uk

Users can get a paid subscription to Spotify or listen to music for free alongside advertising

Warner Music has indicated it may stop licensing its songs to free online streaming services such as Spotify and We7. The record label's chief executive, Edgar Bronfman, said yesterday that allowing people to access free music on such sites was "clearly not positive for the industry".

A spokesman for Warner Music confirmed that this will not affect deals currently in place, meaning songs by artists such as T.I, Fleetwood Mac and Estelle will still be available to hear on the likes of Spotify. He could not confirm how this would affect future deals, except that Warner did not feel ad-supported free services was a sustainable business model for the music industry.

Bronfman's comments come in response to the latest financial figures posted by Warner Music, which show a loss of $17m (�11m) in the last quarter of 2009. CD sales for the third-largest record label in the world continue to shrink, but figures show digital sales were up 8% on last year.

Bronfman expressed his reservation over Spotify, which is currently only available in Europe, entering the US market as a free streaming service. "The 'get all your music you want for free, and then maybe with a few bells and whistles we can move you to a premium price strategy', is not the kind of approach to business that we will be supporting in the future."

Instead, Bronfman suggested Warner Music would be looking to take a bite out of Apple's share of the market with iTunes by offering its own subscription service.

Bronfman also hinted that a merger with EMI, who posted losses of �1.8bn since March last year, was not out of the question.

The true cost of free music downloading - Times Online

Why do people illegally download music? Because they can. The Government recently announced that it has persuaded the internet service providers (ISPs) to sit down with the British Phonographic Industry (BPI) and thrash out measures to curb illegal downloads by creating a voluntary framework that might work within anticipated tighter legislation.

This has been welcomed by most musicians, industry organisations and fair-minded consumers. Reasonable people agree that musicians should be paid for their work. I declare an interest, as deputy chairman of the BPI, although I am writing this in my private capacity as a songwriter, performer and label owner.

But there has been negative comment. Last week I read an article by an otherwise sane and respected musician and journalist who said that downloading music free was like %u201Cdownloading air%u201D, implying that because you can%u2019t see it, it should be free. He also said that it is %u201Cso cheap to get recorded music to the audience that artists no longer need a major label%u201D.

Hating major labels is about as useful as hating film companies and supermarkets. They exist. There will always be dominant players, but there are also about 800 independent record labels in the UK including my own, Dramatico, which has 14 staff and a network of about 50 freelancers around the world. Without the toil and passion of my employees my artists wouldn%u2019t be selling records. Without payment for the music made by our artists we wouldn%u2019t be able to pay our staff. Then the staff would leave and so would the artists.

If you could download a loaf of bread free you would. But you can%u2019t, thank God, because otherwise bakers would cease to exist and there would be no bread to download. Then we%u2019d all be dead, and good riddance to us, because we humans are greedy, thieving, conniving bastards, every last one of us. That%u2019s why there are laws to stop us.

It is tempting to top up your profile by giving your music away free on the web, or as Prince did, by means of a newspaper cover-mounted giveaway to millions of people (his previous album had sold fewer than 90,000 copies in the UK).

But let%u2019s not forget that Prince was paid handsomely for the stunt (at least �150,000). Equally Radiohead, who last year set up an honesty box for their Mercury-nominated album, In Rainbows, had already made millions with their previous albums, so you could argue they could afford to ask people to pay what they wanted to. And anyway, without being being cynical about their motivation, the %u201Cexperiment%u201D also wasn%u2019t bad in attracting attention for the physical release of the CD, which followed a few months later.

It%u2019s nothing new that the entertainment business is %u201Cdog eat dog%u201D. When I came up to London three times a week on the train from Winchester in 1968, a hopeful 18-year-old trying to sell my songs or get signed by, well, anyone really, there were four majors %u2013 EMI, Pye, Phillips and Decca. And there are four today %u2013 EMI, Universal, Warners, Sony/BMG and Universal. It was just as difficult to have a hit then as it is now. Just as hard to get noticed. The business was just as full of arrogant charlatans with kind, helpful faces.

Today it%u2019s a different mixture, though, with different challenges and opportunities. Bands and artists can display their wares on YouTube and MySpace, and record companies can audition artists without even leaving their offices.

But, because of this easier access, telling wheat from chaff is more difficult. Record companies have it easier and harder. It%u2019s easier to get the music to the online customer, but harder to protect it from theft. New business models are being sought and invented all the time. ISPs talking to record companies in order to limit online music theft through their broadband channels is good news for everyone except those who think all music should be free and musicians should go out of business.